11.6. Looking Ahead: Caching on Multicore Processors

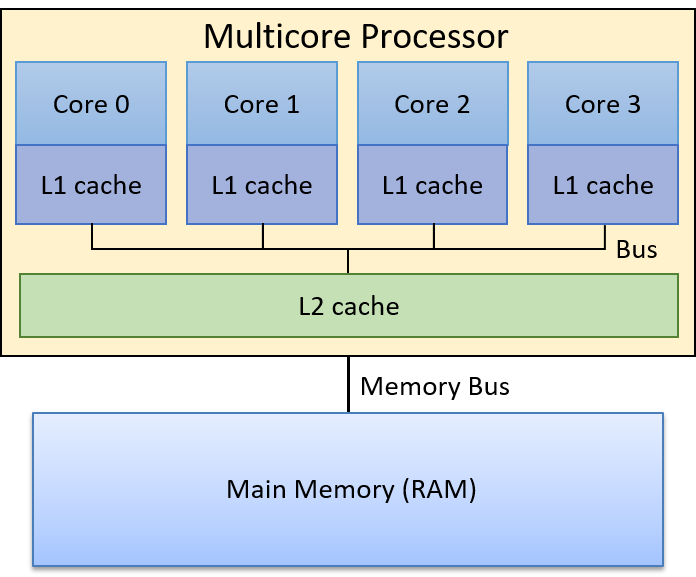

So far our discussion of caching has focused on a single level of cache memory on a single-core processor. Modern processors, however, are multicore with several levels of cache memory. Typically, each core maintains its own private cache memory at the highest level(s) of the memory hierarchy and shares a single cache with all cores at lower levels. Figure 1 shows an example of the memory hierarchy on a four-core processor in which each core contains a private level 1 (L1) cache, and the level 2 (L2) cache is shared by all four cores.

Recall that higher levels of the memory hierarchy are faster to access and smaller in capacity than lower levels of the memory hierarchy. Thus, an L1 cache is smaller and faster than an L2 cache, which in turn is smaller and faster than RAM. Also recall that cache memory stores a copy of a value from a lower level in the memory hierarchy; a value stored in a L1 cache is a copy of the same value stored in the L2 cache, which is a copy of the same value stored in RAM. Thus, higher levels of the memory hierarchy serve as caches for lower levels. As a result, for the example in Figure 1, the L2 cache is a cache of RAM contents, and each core’s L1 cache is a cache of the L2 cache contents.

Each core in a multicore processor simultaneously executes an independent stream of instructions, often from separate programs. Providing each core a private L1 cache allows the core to store copies of the data and instructions exclusively from the instruction stream it’s executing in its fastest cache memory. In other words, each core’s L1 cache stores a copy of only those blocks of memory that are from its execution stream as opposed to competing for space in a single L1 cache shared by all cores. This design yields a higher hit rate in each core’s private L1 cache (in its fastest cache memory) than one in which all cores share a single L1 cache.

Today’s processors often include more than two levels of cache. Three levels are common in desktop systems, with the highest level (L1) typically split into two separate L1 caches, one for program instructions and the other for program data. Lower-level caches are usually unified caches, meaning that they store both program data and instructions. Each core usually maintains a private L1 cache and shares a single L3 cache with all cores. The L2 cache layer, which sits between each core’s private L1 cache and the shared L3 cache, varies substantially in modern CPU designs. The L2 may be a private L2 cache, may be shared by all cores, or may be a hybrid organization with multiple L2 caches, each shared by a subset of cores.

11.6.1. Cache Coherency

Because programs typically exhibit a high degree of locality of reference, it is advantageous for each core to have its own L1 cache to store copies of the data and instructions from the instruction stream it executes. However, multiple L1 caches can result in cache coherency problems. Problems with cache coherency arise when the value of a copy of a block of memory stored in one core’s L1 cache is different than the value of a copy of the same block stored in another core’s L1 cache. This situation occurs when one core writes to a block cached in its L1 cache that is also cached in other core’s L1 caches. Because a cache block contains a copy of memory contents, the system needs to maintain a coherent single value of the memory contents across all copies of the cached block.

Multicore processors implement a cache-coherence protocol to ensure a coherent view of memory that can be cached and accessed by multiple cores. A cache coherency protocol ensures that any core accessing a memory location sees the most recently modified value of that memory location rather than seeing an older (stale) copy of the value that may be stored in its L1 cache.

11.6.2. The MSI Protocol

There are many different cache coherency protocols. Here, we discuss the details of one example, the MSI protocol. The MSI protocol (Modified, Shared, Invalid) adds three flags (or bits) to each cache line. A flag’s value is either clear (0) or set (1). The values of the three flags encode the state of its data block with respect to cache coherency with other cached copies of the block, and their values trigger cache coherency actions on read or write accesses to the data block in the cache line. The three flags used by the MSI protocol are:

-

The M flag that, if set, indicates the block has been modified, meaning that this core has written to its copy of the cached value.

-

The S flag that, if set, indicates that the block is unmodified and can be safely shared, meaning that multiple L1 caches may safely store a copy of the block and read from their copy.

-

The I flag that, if set, indicates if the cached block is invalid or contains stale data (is an older copy of the data that does not reflect the current value of the block of memory).

The MSI protocol is triggered on read and write accesses to cache entries.

On a read access:

-

If the cache block is in the M or S state, the cached value is used to satisfy the read (its copy’s value is the most current value of the block of memory).

-

If the cache block is in the I state, the cached copy is out of date with a newer version of the block, and the block’s new value needs to be loaded into the cache line before the read can be satisfied.

If another core’s L1 cache stores the new value (it stores the value with the M flag set indicating that it stores a modified copy of the value), that other core must first write its value back to the lower level (for example, to the L2 cache). After performing the write-back, it clears the M flag with the cache line (its copy and the copy in the lower-level are now consistent) and sets the S bit to indicate that the block in this cache line is in a state that can be safely cached by other cores (the L1 block is consistent with its copy in the L2 cache and the core read the current value of the block from this L1 copy).

The core that initiated the read access on an line with the I flag set can then load the new value of the block into its cache line. It clears the I flag indicating that the block is now valid and stores the new value of the block, sets the S flag indicating that the block can be safely shared (it stores the latest value and is consistent with other cached copies), and clears the M flag indicating that the L1 block’s value matches that of the copy stored in the L2 cache (a read does not modify the L1 cached copy of the memory).

On a write access:

-

If the block is in the M state, write to the cached copy of the block. No changes to the flags are needed (the block remains in the M state).

-

If the block is in the I or the S state, notify other cores that the block is being written to (modified). Other L1 caches that have the block stored in the S state, need to clear the S bit and set the I bit on their block (their copies of the block are now out of date with the copy that is being written to by the other core). If another L1 cache has the block in the M state, it will write its block back to the lower level, and set its copy to I. The core writing will then load the new value of the block into its L1 cache, set the M flag (its copy will be modified by the write), and clear the I flags (its copy is now valid), and write to the cached block.

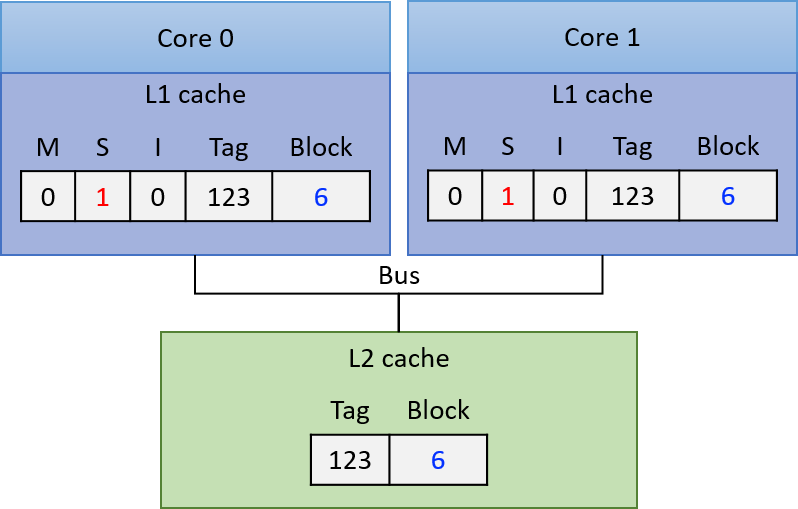

Figure 2 through Figure 4 step through an example of the MSI protocol applied to ensure coherency of read and write accesses to a block of memory that is cached in two core’s private L1 caches. In Figure 2 our example starts with the shared data block copied into both core’s L1 cache with the S flag set, meaning that the L1 cached copies are the same as the value of the block in the L2 cache (all copies store the current value of the block, 6). At this point, both core 0 and core 1 can safely read from the copy stored in their L1 caches without triggering coherency actions (the S flag indicates that their shared copy is up to date).

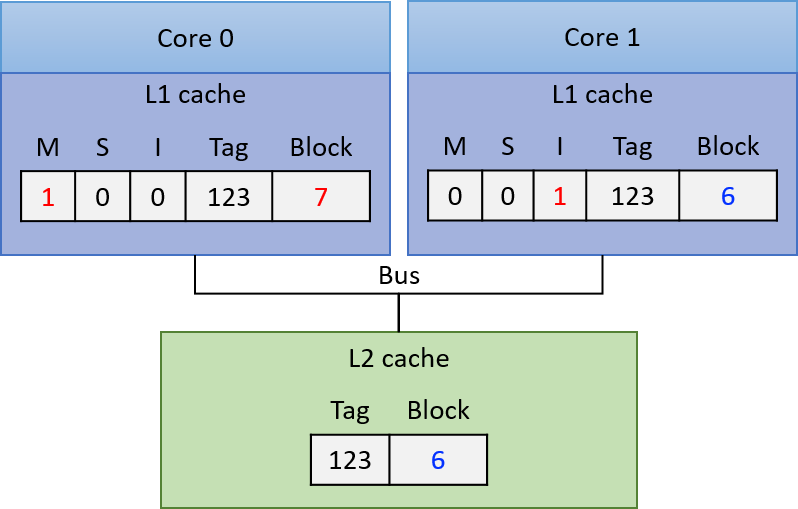

If core 0 next writes to the copy of the block stored in its L1 cache, its L1 cache controller notifies the other L1 caches to invalidate their copy of the block. Core 1’s L1 cache controller then clears the S flag and sets the I flag on its copy, indicating that its copy of the block is stale. Core 0 writes to its copy of the block in its L1 cache (changing its value to 7 in our example), and sets the M flag and clears the S flag on the cache line to indicate that its copy has been modified and stores the current value of the block. At this point, the copy in the L2 cache and in core 1’s L1 cache are stale. The resulting cache state is shown in Figure 3.

At this point, core 0 can safely read from its copy of the cached block because its copy is in the M state, meaning that it stores the most recently written value of the block.

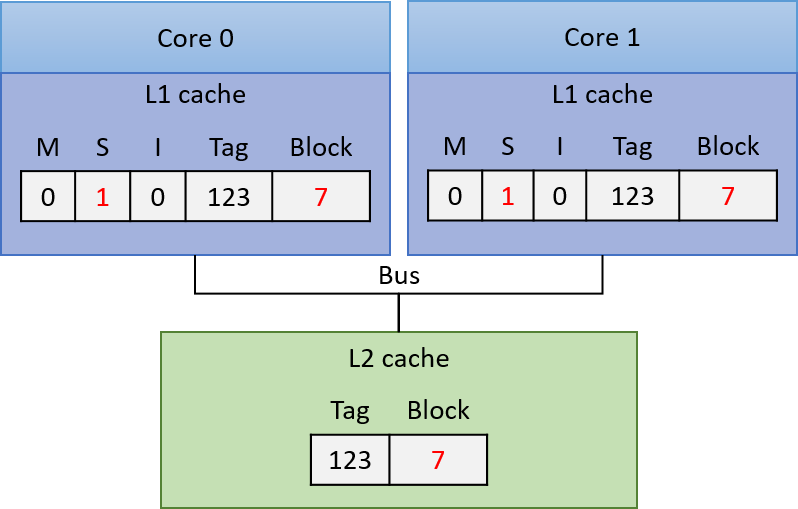

If core 1 next reads from the memory block, the I flag on its L1 cached copy indicates that its L1 copy of the block is stale and cannot be used to satisfy the read. Core 1’s L1 cache controller must first load the new value of the block into the L1 cache before the read can be satisfied. To achieve this, core 0’s L1 cache controller must first write its modified value of the block back to the L2 cache, so that core 1’s L1 cache can read the new value of the block into its L1 cache. The result of these actions, (shown in Figure 4), is that core 0 and core 1’s L1 cached copies of the block are now both stored in the S state, indicating that each core’s L1 copy is up to data and can be safely used to satisfy subsequent reads to the block.

11.6.3. Implementing Cache Coherency Protocols

To implement a cache coherency protocol, a processor needs some mechanism to identify when accesses to one core’s L1 cache contents require coherency state changes involving the other cores' L1 cache contents. One way this mechanism is implemented is through snooping on a bus that is shared by all L1 caches. A snooping cache controller listens (or snoops) on the bus for reads or writes to blocks that it caches. Because every read and write request is in terms of a memory address, a snooping L1 cache controller can identify any read or write from another L1 cache for a block it stores, and can then respond appropriately based on the coherency protocol. For example, it can set the I flag on a cache line when it snoops a write to the same address by another L1 cache. This example is how a write-invalidate protocol would be implemented with snooping.

MSI and other similar protocols such as MESI and MOESI are write-invalidate protocols; that is, protocols that invalidate copies of cached entries on writes. Snooping can also be used by write-update cache coherency protocols, where the new value of a data is snooped from the bus and applied to update all copies stored in other L1 caches.

Instead of snooping, a directory-based cache coherence mechanism can be used to trigger cache coherency protocols. This method scales better than snooping due to performance limitations of multiple cores sharing a single bus. However, directory-based mechanisms require more state to detect when memory blocks are shared, and are slower than snooping.

11.6.4. More about Multicore Caching

The benefits to performance of each core of a multicore processor having its own separate cache(s) at the highest levels of the memory hierarchy, which are used to store copies of only the program data and instructions that it executes, is worth the added extra complexity of the processor needing to implement a cache coherency protocol.

Although cache coherency solves the memory coherency problem on multicore processors with separate L1 caches, there is another problem that can occur as a result of cache coherency protocols on multicore processors. This problem, called false sharing, may occur when multiple threads of a single multithreaded parallel program are running simultaneously across the multiple cores and are accessing memory locations that are near to those accessed by other threads. In section Chapter 14.5, we discuss the false sharing problem and some solutions to it.

For more information and details about hardware caching on multicore processors, including different protocols and how they are implemented, refer to a computer architecture textbook1.

Footnotes

-

One suggestion is "Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware and Software Interface", by David A. Patterson and John L. Hennessy.