16.1. Getting Started Programming in C

Let’s start by looking at a "hello world" program that includes an example of

calling a function from the math library. In Table 1 we compare the C

version of this program to the Java version. The C version might be put in a

file named hello.c (.c is the suffix convention for C source code files),

whereas the Java version might be in a file named HelloWorld.java.

| Java version (HelloWorld.java) | C version (hello.c) |

|---|---|

|

|

Notice that both versions of this program have similar structure and language constructs, albeit with different language syntax.

A few syntactic similarities include:

Comments:

-

Multi-line comments in Java and C begin with

/*and end with*/, and single-line comments begin with//.

Statements:

-

Statements in C and Java end in

;.

Blocks:

-

Both Java and C use

{and}around blocks of related code (for example, function bodies and loop bodies). Good programming style includes indenting statements inside a block.

A few key differences include:

Importing library code:

-

In Java, libraries are included (imported) using

import. -

In C, libraries are included (imported) using

#include. All#includestatements appear at the top of the program, outside of function bodies.

The main function:

-

Both Java and C define

mainfunctions that are the first functions executed when a program is run. In C, there is only onemainfunction defined, and it is automatically called when the C program executes. In Java, thepublic static void mainmethod of the class run on the JVM is executed. -

Java is a purely object oriented language, thus all code must be part of a class (

HelloWorldin this example). Themainfunction is defined as apublic staticmethod in the classHelloWorld(public static void main(String[] args)). By conventionmainis avoidfunction in Java and is passed an array of command line argument strings. -

C is a purely imperative and procedural language, and thus there are no classes in C. As a result, all functions are defined outside of class definitions (there are no class definitions in C). In C,

int main(void){ }defines the main function. Thevoidmeans it doesn’t expect to receive a parameter. Future sections show howmaincan take parameters to receive command line arguments. -

A C program must have a function named

main, and its return type must beint. Themainfunction in C can optionally take a parameter that is a list of strings, one per command line argument (similar to Java), but in its simplest form,mainhas no parameters. In Chapter 2 we showmaindefined to take command line arguments. -

The C

mainfunction has an explicitreturnstatement to return anintvalue (by convention,mainreturns0if the main function is successfully executed without errors).

Output:

-

In Java, the

printandprintlnmethods ofSystem.outcan be used to print a string. The+operator can be used to concatenate values together to create a more complex string (for example,"sqrt(4) is " + Math.sqrt(4)).System.outalso has aprintfmethod to print out a format string with arguments. Values for the placeholders in the format string follow as a comma-separated list of argument values. For example, the second call toSystem.out.printlnin Table 1 could be replaced with the equivalent callSystem.out.printf("sqrt(4) is %f%n", Math.sqrt(4)), where the value ofMath.sqrt(4)will be printed in place of the%fplaceholder in the format string and%n(or\n) is used to specify a newline character. Java additionally has classes that can be used to format different types of values. -

In C, the

printffunction prints a formatted string like Java’sSystem.out.printfmethod (for example, the value ofsqrt(4)will be printed in place of the%fplaceholder in the format string argument, and\nspecifies a newline character).The

printffunction is used to print both format strings and simple string values (C does not have an separate function similar to Java’sSystem.out.println). C’sprintffunction also doesn’t automatically print a newline character at the end. As a result, C programmers need to explicitly specify a newline character (\n) in the format string when a newline is desired in the output.

16.1.1. Compiling and Running C Programs

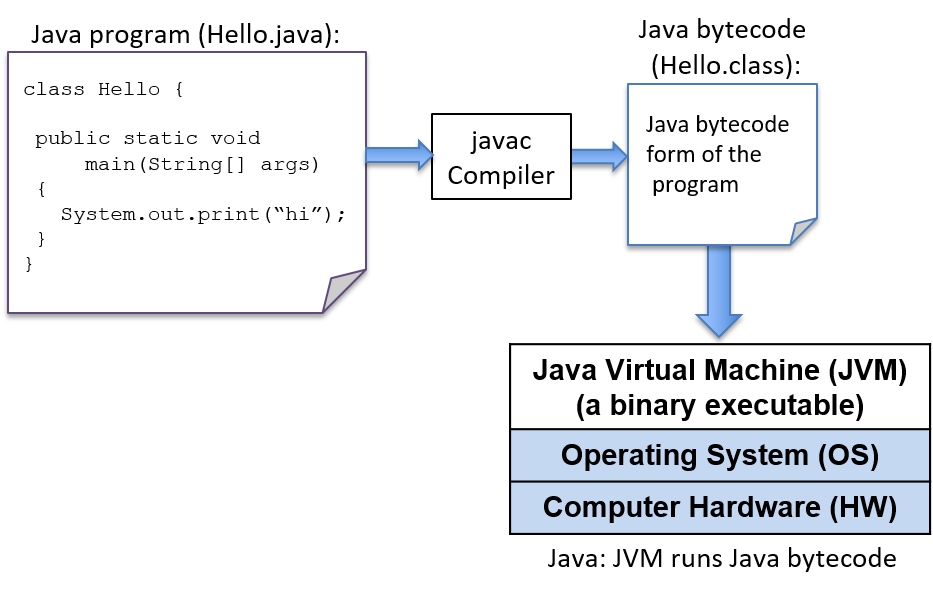

Java programs run on the Java virtual machine (JVM). The JVM is a program

that runs directly on the underlying computer system. To run a Java program,

it is first compiled (translated) by the Java compiler (javac) from its

source code (HelloWorld.java) form into Java bytecode form. For example

($ is the Linux shell prompt):

$ javac HelloWorld.javaIf successful, javac creates a new file, HelloWorld.class,

that contains the Java bytecode translation of the program that the JVM

can run. For example:

$ java HelloWorldThe JVM is a program that is in a form that can be run directly on the underlying system (this form is called binary executable) and takes as input the Java class that it runs (Figure 1). Java bytecode is very portable in the sense that it can run on any computer system with a JVM. However, because Java bytecode does not run directly on the underlying computer system, a Java program may not run as efficiently as programs that run directly on the underlying system.

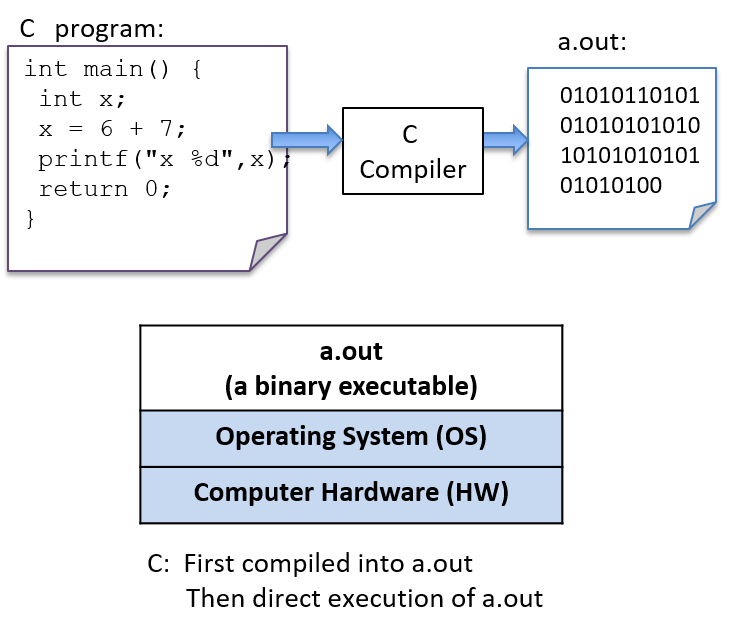

To run a C program, it must first be translated into a form that a computer system can directly execute. The C compiler, similar to the Java compiler, is a program that translates C source code into a binary executable form that the computer system can directly execute. A binary executable consists of a series of 0’s and 1’s in a well-defined format that a computer can run; unlike Java bytecode that requires the JVM to run, the binary executable runs directly on the underlying system.

For example, to run the C program hello.c on a Unix system, the C code must

first be compiled by a C compiler (for example, the GNU C

compiler, GCC) that produces a binary executable (by default named a.out).

The binary executable version of the program can then be run directly on the

system (Figure 2):

$ gcc hello.c

$ ./a.out(Note that some C compilers might need to be explicitly told to link in the

math library: -lm):

$ gcc hello.c -lm

Detailed Steps

In general, the following sequence describes the necessary steps for editing, compiling, and running a C program on a Unix system:

-

Using a text editor (for example,

vim), write and save your C source code program in a file (e.g.,hello.c):$ vim hello.c

-

Compile the source to an executable form, and then run it. The most basic syntax for compiling with

gccis:$ gcc <input_source_file>

If compilation yields no errors, the compiler creates a binary executable file

named a.out. The compiler also allows you to specify the name of the binary

executable file to generate using the -o flag:

$ gcc -o <output_executable_file> <input_source_file>

For example, this command instructs gcc to compile hello.c into an

executable file named hello:

$ gcc -o hello hello.c

We can invoke the executable program using ./hello:

$ ./hello

Any changes made to the C source code (the hello.c file) must be recompiled

with gcc to produce a new version of hello. If the compiler detects any

errors during compilation, the ./hello file won’t be created/re-created (but

beware, an older version of the file from a previous successful compilation

might still exist).

Often when compiling with gcc, you want to include several command line

options. For example, these options enable more compiler warnings and build a

binary executable with extra debugging information:

$ gcc -Wall -g -o hello hello.c

Because the gcc command line can be long, frequently the make utility is

used to simplify compiling C programs and for cleaning up files created by

gcc.

Using make

and writing Makefiles are important skills that you will develop as you build

up experience with C programming.

We cover compiling and linking with C library code in more detail at the end of Chapter 2.

16.1.2. Variables and C Numeric Types

Like Java, C uses variables as named storage locations for holding data. Thinking about the scope and type of program variables is important to understand the semantics of what your program will do when you run it. A variable’s scope defines when the variable has meaning (that is, where and when in your program it can be used) and its lifetime (that is, it could persist for the entire run of a program or only during a function activation). A variable’s type defines the range of values that it can represent and how those values will be interpreted when performing operations on its data.

In both Java and C, all variables must be declared before they can be used. To declare a variable in C, use the following syntax:

type_name variable_name;A variable can have only a single type. The basic C types include char,

int, float, and double. By convention, C variables should be declared at

the beginning of their scope (at the top of a { } block), before any C

statements in that scope.

Below is an example C code snippet that shows declarations and uses of variables of some different types. We discuss types and operators in more detail after the example.

{

/* 1. Define variables in this block's scope at the top of the block. */

int x; // declares x to be an int type variable and allocates space for it

int i, j, k; // can define multiple variables of the same type like this

char letter; // a char stores a single-byte integer value

// it is often used to store a single ASCII character

// value (the ASCII numeric encoding of a character)

// a char in C is a different type than a string in C

float winpct; // winpct is declared to be a float type

double pi; // the double type is more precise than float

/* 2. After defining all variables, you can use them in C statements. */

x = 7; // x stores 7 (initialize variables before using their value)

k = x + 2; // use x's value in an expression

letter = 'A'; // a single quote is used for single character value

letter = letter + 1; // letter stores 'B' (ASCII value one more than 'A')

pi = 3.1415926;

winpct = 11 / 2.0; // winpct gets 5.5, winpct is a float type

j = 11 / 2; // j gets 5: int division truncates after the decimal

x = k % 2; // % is C's mod operator, so x gets 9 mod 2 (1)

}16.1.3. C Types

Unlike Java, C does not have an extensive set of class libraries defining complex data types. Instead, C supports a small set of built-in data types, and it provides a few ways in which programmers can construct basic collections of types (arrays and structs). From these basic building blocks, a C programmer can build complex data structures.

C defines a set of basic types for storing numeric values. Here are some examples of numeric literal values of different C types:

8 // the int value 8

3.4 // the double value 3.4

'h' // the char value 'h' (its value is 104, the ASCII value of h)The C char type stores a numeric value. However, it’s often used by

programmers to store the value of an ASCII character. A character literal

value is specified in C as a single character between single quotes.

C doesn’t support a string type, but programmers can create strings from the

char type and C’s support for constructing arrays of values, which we discuss

in later sections. C does, however, support a way of expressing string literal

values in programs: a string literal is any sequence of characters between

double quotes. C programmers often pass string literals as the format string

argument to printf:

printf("this is a C string\n");Java and C both support string and char type values. Typically, Java char values are 16-bit unicode values and C’s are 8-bit ascii values.

In both Java and C a string and a char are two very different types, and they

evaluate differently. This difference is illustrated by contrasting a C string

literal that contains one character with a C char literal. For example:

'h' // this is a char literal value (its value is 104, the ASCII value of h)

"h" // this is a string literal value (its value is NOT 104, it is not a char)We discuss C strings and char variables in more detail in the

Strings section later in

this chapter. Here, we’ll mainly focus on C’s numeric types.

C Numeric Types

C supports several different types for storing numeric values. The types

differ in the format of the numeric values they represent. For example, the

float and double types can represent real values, int represents signed

integer values, and unsigned int represents unsigned integer values. Real

values are positive or negative values with a decimal point, such as -1.23 or

0.0056. Signed integers store positive, negative, or zero integer values,

such as -333, 0, or 3456. Unsigned integers store strictly nonnegative

integer values, such as 0 or 1234.

C’s numeric types also differ in the range and precision of the values they can represent. The range or precision of a value depends on the number of bytes associated with its type. Types with more bytes can represent a larger range of values (for integer types), or higher-precision values (for real types), than types with fewer bytes.

Table 2 shows the number of storage bytes, the kind of numeric values stored, and how to declare a variable for a variety of common C numeric types (note that these are typical sizes — the exact number of bytes depends on the hardware architecture).

| Type name | Usual size | Values stored | How to declare |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 byte |

integers |

|

|

2 bytes |

signed integers |

|

|

4 bytes |

signed integers |

|

|

4 or 8 bytes |

signed integers |

|

|

8 bytes |

signed integers |

|

|

4 bytes |

signed real numbers |

|

|

8 bytes |

signed real numbers |

|

C also provides unsigned versions of the integer numeric types (char,

short, int, long, and long long). To declare a variable as unsigned,

add the keyword unsigned before the type name. For example:

int x; // x is a signed int variable

unsigned int y; // y is an unsigned int variableThe C standard doesn’t specify whether the char type is signed or unsigned.

As a result, some implementations might implement char as signed integer

values and others as unsigned. It’s good programming practice to explicitly

declare unsigned char if you want to use the unsigned version of a char

variable.

The exact number of bytes for each of the C types might vary from one

architecture to the next. The sizes in Table 2 are minimum (and

common) sizes for each type. You can print the exact size on a given machine

using C’s sizeof operator, which takes the name of a type as an argument and

evaluates to the number of bytes used to store that type. For example:

printf("number of bytes in an int: %lu\n", sizeof(int));

printf("number of bytes in a short: %lu\n", sizeof(short));The sizeof operator evaluates to an unsigned long value, so in the call to

printf, use the placeholder %lu to print its value. On most architectures

the output of these statements will be:

number of bytes in an int: 4 number of bytes in a short: 2

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators combine values of numeric types. The resulting type of

the operation is based on the types of the operands. For example, if two int

values are combined with an arithmetic operator, the resulting type is also an

integer.

C performs automatic type conversion when an operator combines operands of two

different types. For example, if an int operand is combined with a float

operand, the integer operand is first converted to its floating-point

equivalent before the operator is applied, and the type of the operation’s

result is float.

The following arithmetic operators can be used on most numeric type operands:

-

add (

+) and subtract (-) -

multiply (

*), divide (/), and mod (%):The mod operator (

%) can only take integer-type operands (int,unsigned int,short, and so on).If both operands are

inttypes, the divide operator (/) performs integer division (the resulting value is anint, truncating anything beyond the decimal point from the division operation). For example8/3evaluates to2.If one or both of the operands are

float(ordouble),/performs real division and evaluates to afloat(ordouble) result. For example,8 / 3.0evaluates to approximately2.666667. -

assignment (

=):variable = value of expression; // e.g., x = 3 + 4;

-

assignment with update (

+=,-=,*=,/=, and%=):variable op= expression; // e.g., x += 3; is shorthand for x = x + 3;

-

increment (

++) and decrement (--):variable++; // e.g., x++; assigns to x the value of x + 1

|

Pre- vs. Post-increment

The operators

In many cases, it doesn’t matter which you use because the value of the incremented or decremented variable isn’t being used in the statement. For example, these two statements are equivalent (although the first is the most commonly used syntax for this statement): In some cases, the context affects the outcome (when the value of the incremented or decremented variable is being used in the statement). For example: Code like the preceding example that uses an arithmetic expression with an

increment operator is often hard to read, and it’s easy to get wrong. As a

result, it’s generally best to avoid writing code like this; instead, write

separate statements for exactly the order you want. For example, if you want

to first increment Instead of writing this: write it as two separate statements: |