14.4.2. Advanced Topics

Gustafson-Barsis Law

In 1988, John L. Gustafson, a computer scientist and researcher at Sandia National Labs, wrote a paper called "Reevaluating Amdahl’s Law1". In this paper, Gustafson calls to light a critical assumption that was made about the execution of a parallel program that is not always true.

Specifically, Amdahl’s law implies that the number of compute cores c and the fraction of a program that is parallelizable P are independent of each other. Gustafson notes that this "is virtually never the case."1 While benchmarking a program’s performance by varying the number of cores on a fixed set of data is a useful academic exercise, in the real world, more cores (or processors, as examined in our discussion of distributed memory) are added as the problem grows large. "It may be most realistic," Gustafson writes1, "to assume run time, not problem size, is constant."

Thus, according to Gustafson, it is most accurate to say that "The amount of work that can be done in parallel varies linearly with the number of processors."1

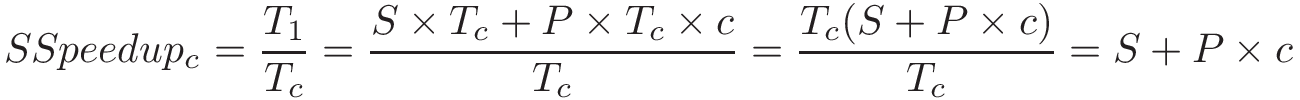

Consider a parallel program that takes time Tc to run on a system with c cores. Let S represent the fraction of the program execution that is necessarily serial and takes S × Tc time to run. Thus, the parallelizable fraction of the program execution, P = 1 - S, takes P × Tc time to run on c cores.

When the same program is run on just one core, the serial fraction of the code still takes S x Tc (assuming all other conditions are equal). However, the parallelizable fraction (which was divided between c cores) now has to be executed by just one core to run serially and takes P × Tc × c time. In other words, the parallel component will take c times as long on a single-core system. It follows that the scaled speedup would be:

This shows that the scaled speedup increases linearly with the number of compute units.

Consider our prior example in which 99% of a program is parallelizable (i.e., P = 0.99). Applying the scaled speedup equation, the theoretical speedup on 100 processors would be 99.01. On 1,000 processors, it would be 990.01. Notice that the efficiency stays constant at P.

As Gustafson concludes, "speedup should be measured by scaling the problem to the number of processors, not by fixing a problem size."1 Gustafson’s result is notable because it shows that it is possible to get increasing speedup by updating the number of processors. As a researcher working in a national supercomputing facility, Gustafson was more interested in doing more work in a constant amount of time. In several scientific fields, the ability to analyze more data usually leads to higher accuracy or fidelity of results. Gustafson’s work showed that it was possible to get large speedups on large numbers of processors, and revived interest in parallel processing2.

Scalability

We describe a program as scalable if we see improving (or constant) performance as we increase the number of resources (cores, processors) or the problem size. Two related concepts are strong scaling and weak scaling. It is important to note that "weak" and "strong" in this context do not indicate the quality of a program’s scalability, but are simply different ways to measure scalability.

We say that a program is strongly scalable if increasing the number of cores/processing units on a fixed problem size yields an improvement in performance. A program displays strong linear scalability if, when run on n cores, the speedup is also n. Of course, Amdahl’s Law guarantees that after some point, adding additional cores makes little sense.

We say that a program is weakly scalable if increasing the size of the data at the same rate as the number of cores (i.e., if there is a fixed data size per core/processor) results in constant or an improvement in performance. We say a program displays weak linear scalability if we see an improvement of n if the work per core is scaled up by a factor of n.

General Advice Regarding Measuring Performance

We conclude our discussion on performance with some notes about benchmarking and performance on hyperthreaded cores.

- Run a program multiple times when benchmarking.

-

In many of the examples shown thus far in this book, we run a program only once to get a sense of its runtime. However, this is not sufficient for formal benchmarks. Running a program once is never an accurate measure of a program’s true runtime! Context switches and other running processes can temporarily cause the runtime to radically fluctuate. Therefore, it is always best to run a program several times and report an average runtime together with as many details as feasible, including number of runs, observed variability of the measurements (e.g., error bars, minimum, maximum, median, standard deviation) and conditions under which the measurements were taken.

- Be careful where you measure timing.

-

The

gettimeofdayfunction is useful in helping to accurately measure the time a program takes to run. However, it can also be abused. Even though it may be tempting to place thegettimeofdaycall around only the thread creation and joining component inmain, it is important to consider what exactly you are trying to time. For example, if a program reads in an external data file as a necessary part of its execution, the time for file reading should likely be included in the program’s timing. - Be aware of the impact of hyperthreaded cores.

-

As discussed in the introduction to this chapter and hardware multithreading section, hyper-threaded (logical) cores are capable of executing multiple threads on a single core. In a quad-core system with two logical threads per core, we say there are eight hyperthreaded cores on the system. Running a program in parallel on eight logical cores in many cases yields better wall time than running a program on four cores. However, due to the resource contention that usually occurs with hyperthreaded cores, you may see a dip in core efficiency and nonlinear speedup.

- Beware of resource contention.

-

When benchmarking, it’s always important to consider what other processes and threaded applications are running on the system. If your performance results ever look a bit strange, it is worth quickly running

topto see whether there are any other users also running resource-intensive tasks on the same system. If so, try using a different system to benchmark (or wait until the system is not so heavily used).

References

-

John Gustafson. "Reevaluating Amdahl’s law". Communications of the ACM 31(5), pp. 532—533. ACM. 1988.

-

Caroline Connor. "Movers and Shakers in HPC: John Gustafson" HPC Wire. http://www.hpcwire.com/hpcwire/2010-10-20/movers_and_shakers_in_hpc_john_gustafson.html