0. Introduction

Dive into the fabulous world of computer systems! Understanding what a computer system is and how it runs your programs can help you to design code that runs efficiently and that can make the best use of the power of the underlying system. In this book, we take you on a journey through computer systems. You will learn how your program written in a high-level programming language (we use C) executes on a computer. You will learn how program instructions translate into binary and how circuits execute their binary encoding. You will learn how an operating system manages programs running on the system. You will learn how to write programs that can make use of multicore computers. Throughout, you will learn how to evaluate the systems costs associated with program code and how to design programs to run efficiently.

What Is a Computer System?

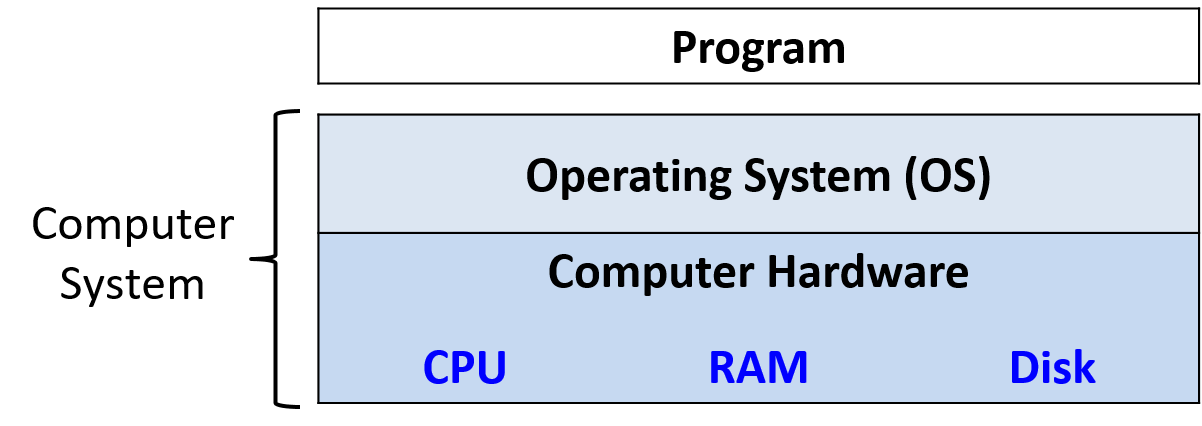

A computer system combines the computer hardware and special system software that together make the computer usable by users and programs. Specifically, a computer system has the following components (see Figure 1):

-

Input/output (IO) ports enable the computer to take information from its environment and display it back to the user in some meaningful way.

-

A central processing unit (CPU) runs instructions and computes data and memory addresses.

-

Random access memory (RAM) stores the data and instructions of running programs. The data and instructions in RAM are typically lost when the computer system loses power.

-

Secondary storage devices like hard disks store programs and data even when power is not actively being provided to the computer.

-

An operating system (OS) software layer lies between the hardware of the computer and the software that a user runs on the computer. The OS implements programming abstractions and interfaces that enable users to easily run and interact with programs on the system. It also manages the underlying hardware resources and controls how and when programs execute. The OS implements abstractions, policies, and mechanisms to ensure that multiple programs can simultaneously run on the system in an efficient, protected, and seamless manner.

The first four of these define the computer hardware component of a computer system. The last item (the operating system) represents the main software part of the computer system. There may be additional software layers on top of an OS that provide other interfaces to users of the system (e.g., libraries). However, the OS is the core system software that we focus on in this book.

We focus specifically on computer systems that have the following qualities:

-

They are general purpose, meaning that their function is not tailored to any specific application.

-

They are reprogrammable, meaning that they support running a different program without modifying the computer hardware or system software.

To this end, many devices that may "compute" in some form do not fall into the category of a computer system. Calculators, for example, typically have a processor, limited amounts of memory, and I/O capability. However, calculators typically do not have an operating system (advanced graphing calculators like the TI-89 are a notable exception to this rule), do not have secondary storage, and are not general purpose.

Another example that bears mentioning is the microcontroller, a type of integrated circuit that has many of the same capabilities as a computer. Microcontrollers are often embedded in other devices (such as toys, medical devices, cars, and appliances), where they control a specific automatic function. Although microcontrollers are general purpose, reprogrammable, contain a processor, internal memory, secondary storage, and are I/O capable, they lack an operating system. A microcontroller is designed to boot and run a single specific program until it loses power. For this reason, a microcontroller does not fit our definition of a computer system.

What Do Modern Computer Systems Look Like?

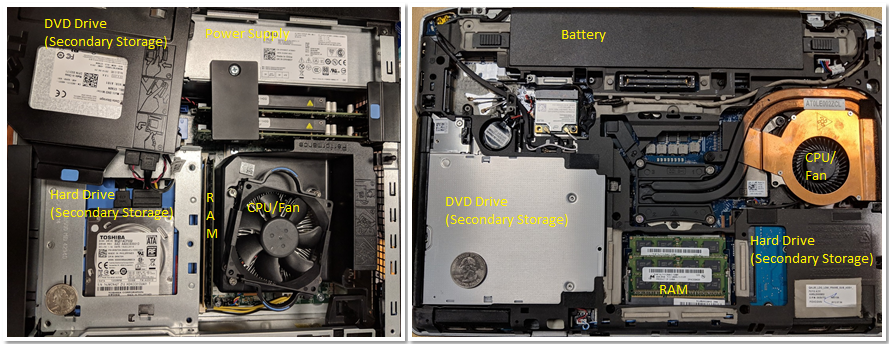

Now that we have established what a computer system is (and isn’t), let’s discuss what computer systems typically look like. Figure 2 depicts two types of computer hardware systems (excluding peripherals): a desktop computer (left) and a laptop computer (right). A U.S. quarter on each device gives the reader an idea of the size of each unit.

Notice that both contain the same hardware components, though some of the components may have a smaller form factor or be more compact. The DVD/CD bay of the desktop was moved to the side to show the hard drive underneath — the two units are stacked on top of each other. A dedicated power supply helps provide the desktop power.

In contrast, the laptop is flatter and more compact (note that the quarter in this picture appears a bit bigger). The laptop has a battery and its components tend to be smaller. In both the desktop and the laptop, the CPU is obscured by a heavyweight CPU fan, which helps keep the CPU at a reasonable operating temperature. If the components overheat, they can become permanently damaged. Both units have dual inline memory modules (DIMM) for their RAM units. Notice that laptop memory modules are significantly smaller than desktop modules.

In terms of weight and power consumption, desktop computers typically consume 100 - 400 W of power and typically weigh anywhere from 5 to 20 pounds. A laptop typically consumes 50 - 100 W of power and uses an external charger to supplement the battery as needed.

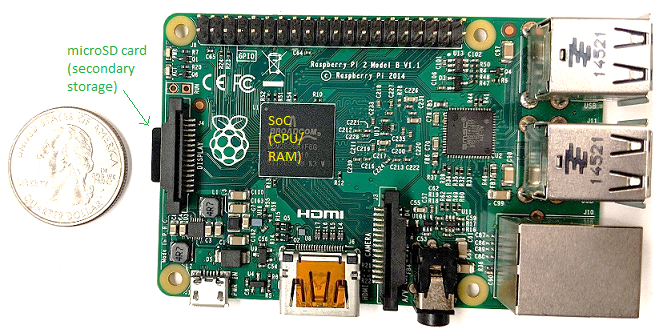

The trend in computer hardware design is toward smaller and more compact devices. Figure 3 depicts a Raspberry Pi single-board computer. A single-board computer (SBC) is a device in which the entirety of the computer is printed on a single circuit board.

The Raspberry Pi SBC contains a system-on-a-chip (SoC) processor with integrated RAM and CPU, which encompasses much of the laptop and desktop hardware shown in Figure 2. Unlike laptop and desktop systems, the Raspberry Pi is roughly the size of a credit card, weighs 1.5 ounces (about a slice of bread), and consumes about 5 W of power. The SoC technology found on the Raspberry Pi is also commonly found in smartphones. In fact, the smartphone is another example of a computer system!

Lastly, all of the aforementioned computer systems (Raspberry Pi and smartphones included) have multicore processors. In other words, their CPUs are capable of executing multiple programs simultaneously. We refer to this simultaneous execution as parallel execution. Basic multicore programming is covered in Chapter 14 of this book.

All of these different types of computer hardware systems can run one or more general purpose operating systems, such as macOS, Windows, or Unix. A general-purpose operating system manages the underlying computer hardware and provides an interface for users to run any program on the computer. Together these different types of computer hardware running different general-purpose operating systems make up a computer system.

What You Will Learn In This Book

By the end of this book, you will know the following:

How a computer runs a program: You will be able to describe, in detail, how a program expressed in a high-level programming language gets executed by the low-level circuitry of the computer hardware. Specifically, you will know:

-

how program data gets encoded into binary and how the hardware performs arithmetic on it

-

how a compiler translates C programs into assembly and binary machine code (assembly is the human-readable form of binary machine code)

-

how a CPU executes binary instructions on binary program data, from basic logic gates to complex circuits that store values, perform arithmetic, and control program execution

-

how the OS implements the interface for users to run programs on the system and how it controls program execution on the system while managing the system’s resources.

How to evaluate systems costs associated with a program’s performance: A program runs slowly for a number of reasons. It could be a bad algorithm choice or simply bad choices on how your program uses system resources. You will understand the Memory Hierarchy and its effects on program performance, and the operating systems costs associated with program performance. You will also learn some valuable tips for code optimization. Ultimately, you will be able to design programs that use system resources efficiently, and you will know how to evaluate the systems costs associated with program execution.

How to leverage the power of parallel computers with parallel programming: Taking advantage of parallel computing is important in today’s multicore world. You will learn to exploit the multiple cores on your CPU to make your program run faster. You will know the basics of multicore hardware, the OS’s thread abstraction, and issues related to multithreaded parallel program execution. You will have experience with parallel program design and writing multithreaded parallel programs using the POSIX thread library (Pthreads). You will also have an introduction to other types of parallel systems and parallel programming models.

Along the way, you will also learn many other important details about computer systems, including how they are designed and how they work. You will learn important themes in systems design and techniques for evaluating the performance of systems and programs. You’ll also master important skills, including C and assembly programming and debugging.

Getting Started with This Book

A few notes about languages, book notation, and recommendations for getting started reading this book:

Linux, C, and the GNU Compiler

We use the C programming language in examples throughout the book. C is a high-level programming language like Java and Python, but it is less abstracted from the underlying computer system than many other high-level languages. As a result, C is the language of choice for programmers who want more control over how their program executes on the computer system.

The code and examples in this book are compiled using the GNU C Compiler (GCC) and run on the Linux operating system. Although not the most common mainstream OS, Linux is the dominant OS on supercomputing systems and is arguably the most commonly used OS by computer scientists.

Linux is also free and open source, which contributes to its popular use in these settings. A working knowledge of Linux is an asset to all students in computing. Similarly, GCC is arguably the most common C compiler in use today. As a result, we use Linux and GCC in our examples. However, other Unix systems and compilers have similar interfaces and functionality.

In this book, we encourage you to type along with the listed examples. Linux commands appear in blocks like the following:

$

The $ represents the command prompt. If you see a box that looks

like

$ uname -a

this is an indication to type uname -a on the command line. Make sure that

you don’t type the $ sign!

The output of a command is usually shown directly after the command in a command line listing.

As an example, try typing in uname -a. The output of this command varies from system to

system. Sample output for a 64-bit system is shown here.

$ uname -a Linux Fawkes 4.4.0-171-generic #200-Ubuntu SMP Tue Dec 3 11:04:55 UTC 2019 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux

The uname command prints out information about a particular system. The -a flag prints out all relevant information associated with the system

in the following order:

-

The kernel name of the system (in this case Linux)

-

The hostname of the machine (e.g., Fawkes)

-

The kernel release (e.g., 4.4.0-171-generic)

-

The kernel version (e.g., #200-Ubuntu SMP Tue Dec 3 11:04:55 UTC 2019)

-

The machine hardware (e.g., x86_64)

-

The type of processor (e.g., x86_64)

-

The hardware platform (e.g., x86_64)

-

The operating system name (e.g., GNU/Linux)

You can learn more about the uname command or any other Linux command by prefacing the command with man,

as shown here:

$ man uname

This command brings up the manual page associated with the uname command. To quit out of this interface,

press the q key.

While a detailed coverage of Linux is beyond the scope of this book, readers can get a good introduction in the online Appendix 2 - Using UNIX. There are also several online resources that can give readers a good overview. One recommendation is "The Linux Command Line"1.

Other Types of Notation and Callouts

Aside from the command line and code snippets, we use several other types of "callouts" to represent content in this book.

The first is the aside. Asides are meant to provide additional context to the text, usually historical. Here’s a sample aside:

The second type of callout we use in this text is the note. Notes are used to highlight important information, such as the use of certain types of notation or suggestions on how to digest certain information. A sample note is shown below:

|

How to do the readings in this book

As a student, it is important to do the readings in the textbook. Notice that we say "do" the readings, not simply "read" the readings. To "read" a text typically implies passively imbibing words off a page. We encourage students to take a more active approach. If you see a code example, try typing it in! It’s OK if you type in something wrong, or get errors; that’s the best way to learn! In computing, errors are not failures — they are simply experience. |

The last type of callout that students should pay specific attention to is the warning. The authors use warnings to highlight things that are common "gotchas" or a common cause of consternation among our own students. Although all warnings may not be equally valuable to all students, we recommend that you review warnings to avoid common pitfalls whenever possible. A sample warning is shown here:

|

This book contains puns

The authors (especially the first author) are fond of puns and musical parodies related to computing (and not necessarily good ones). Adverse reactions to the authors' sense of humor may include (but are not limited to) eye-rolling, exasperated sighs, and forehead slapping. |

If you are ready to get started, please continue on to the first chapter as we dive into the wonderful world of C. If you already know some C programming, you may want to start with Chapter 4 on binary representation, or continue with more advanced C programming in Chapter 2.

We hope you enjoy your journey with us!

References

-

William Shotts. "The Linux Command Line", LinuxCommand.org, https://linuxcommand.org/