1.6. Structs

Arrays and structs are the two ways in which C supports creating collections of data elements. Arrays are used to create an ordered collection of data elements of the same type, whereas structs are used to create a collection of data elements of different types. A C programmer can combine array and struct building blocks in many different ways to create more complex data types and structures. This section introduces structs, and in the next chapter we characterize structs in more detail and show how you can combine them with arrays.

C is not an object-oriented language; thus, it doesn’t support classes. It

does, however, support defining structured types, which are like the data part

of classes. A struct is a type used to represent a heterogeneous collection

of data; it’s a mechanism for treating a set of different types as a single,

coherent unit. C structs provide a level of abstraction on top of individual

data values, treating them as a single type. For example, a student has a

name, age, grade point average (GPA), and graduation year. A programmer could

define a new struct type to combine those four data elements into a single

struct student variable that contains a name value (type char [], to hold a

string), an age value (type int), a GPA value (type float), and a

graduation year value (type int). A single variable of this struct type can

store all four pieces of data for a particular student; for example, ("Freya",

19, 3.7, 2021).

There are three steps to defining and using struct types in C programs:

-

Define a new

structtype that represents the structure. -

Declare variables of the new

structtype. -

Use dot (

.) notation to access individual field values of the variable.

1.6.1. Defining a Struct Type

A struct type definition should appear outside of any function, typically

near the top of the program’s .c file. The syntax for defining a new struct

type is the following (struct is a reserved keyword):

struct <struct_name> {

<field 1 type> <field 1 name>;

<field 2 type> <field 2 name>;

<field 3 type> <field 3 name>;

...

};Here’s an example of defining a new struct studentT type for storing student

data:

struct studentT {

char name[64];

int age;

float gpa;

int grad_yr;

};This struct definition adds a new type to C’s type system, and the type’s name is

struct studentT. This struct defines four fields, and each field definition

includes the type and name of the field. Note that in this example, the name

field’s type is a character array, for

use

as a string.

1.6.2. Declaring Variables of Struct Types

Once the type has been defined, you can declare variables of the new type,

struct studentT. Note that unlike the other types we’ve encountered so far

that consist of just a single word (for example, int, char, and float),

the name of our new struct type is two words, struct studentT.

struct studentT student1, student2; // student1, student2 are struct studentT1.6.3. Accessing Field Values

To access field values in a struct variable, use dot notation:

<variable name>.<field name>When accessing structs and their fields, carefully consider the types of the

variables you’re using. Novice C programmers often introduce bugs into their

programs by failing to account for the types of struct fields.

Table 1 shows the types of several expressions surrounding our

struct studentT type.

| Expression | C type |

|---|---|

|

|

|

integer ( |

|

array of characters ( |

|

character ( |

Here are some examples of assigning a struct studentT variable’s fields:

// The 'name' field is an array of characters, so we can use the 'strcpy'

// string library function to fill in the array with a string value.

strcpy(student1.name, "Kwame Salter");

// The 'age' field is an integer.

student1.age = 18 + 2;

// The 'gpa' field is a float.

student1.gpa = 3.5;

// The 'grad_yr' field is an int

student1.grad_yr = 2020;

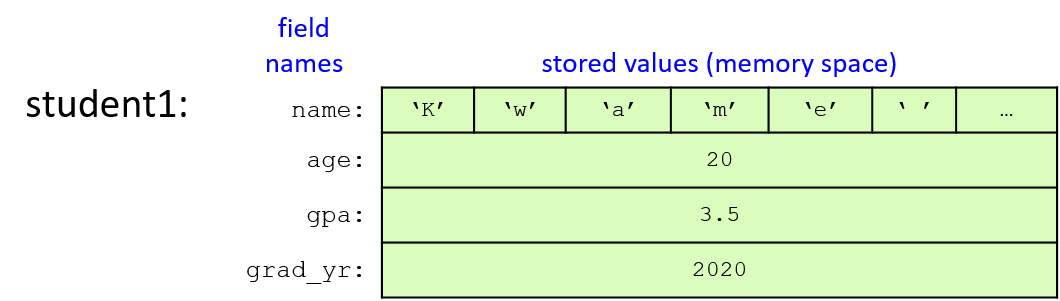

student2.grad_yr = student1.grad_yr;Figure 1 illustrates the layout of the student1 variable in

memory after the field assignments in the preceding example. Only the struct

variable’s fields (the areas in boxes) are stored in memory. The field names

are labeled on the figure for clarity, but to the C compiler, fields are simply

storage locations or offsets from the start of the struct variable’s memory.

For example, based on the definition of a struct studentT, the compiler knows

that to access the field named gpa, it must skip past an array of 64

characters (name) and one integer (age). Note that in the figure, the

name field only depicts the first six characters of the 64-character array.

C struct types are lvalues, meaning they can appear on the left side of an assignment statement. Thus, a struct variable can be assigned the value of another struct variable using a simple assignment statement. The field values of the struct on the right side of the assignment statement are copied to the field values of the struct on the left side of the assignment statement. In other words, the contents of memory of one struct are copied to the memory of the other. Here’s an example of assigning a struct’s values in this way:

student2 = student1; // student2 gets the value of student1

// (student1's field values are copied to

// corresponding field values of student2)

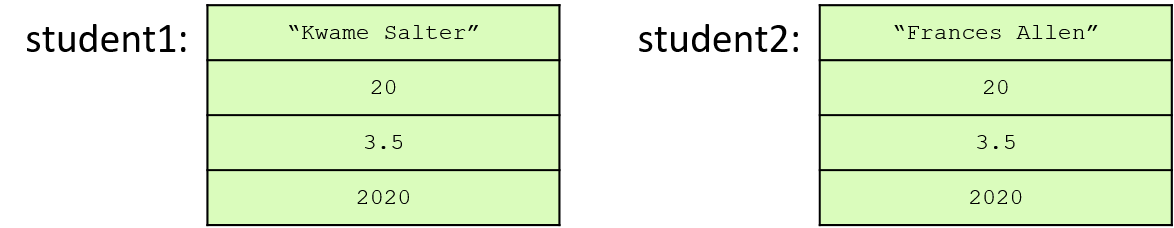

strcpy(student2.name, "Frances Allen"); // change one field valueFigure 2 shows the values of the two student variables after the

assignment statement and call to strcpy have executed. Note that the figure

depicts the name fields as the string values they contain rather than the

full array of 64 characters.

C provides a sizeof operator that takes a type and returns the number of

bytes used by the type. The sizeof operator can be used on any C type,

including struct types, to see how much memory space a variable of that type

needs. For example, we can print the size of a struct studentT type:

// Note: the `%lu` format placeholder specifies an unsigned long value.

printf("number of bytes in student struct: %lu\n", sizeof(struct studentT));When run, this line should print out a value of at least 76 bytes, because 64

characters are in the name array (1 byte for each char), 4 bytes for the

int age field, 4 bytes for the float gpa field, and 4 bytes for the

int grad_yr field. The exact number of bytes might be larger than 76 on

some machines.

Here’s a full example program that

defines and demonstrates the use of our struct studentT type:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

// Define a new type: struct studentT

// Note that struct definitions should be outside function bodies.

struct studentT {

char name[64];

int age;

float gpa;

int grad_yr;

};

int main(void) {

struct studentT student1, student2;

strcpy(student1.name, "Kwame Salter"); // name field is a char array

student1.age = 18 + 2; // age field is an int

student1.gpa = 3.5; // gpa field is a float

student1.grad_yr = 2020; // grad_yr field is an int

/* Note: printf doesn't have a format placeholder for printing a

* struct studentT (a type we defined). Instead, we'll need to

* individually pass each field to printf. */

printf("name: %s age: %d gpa: %g, year: %d\n",

student1.name, student1.age, student1.gpa, student1.grad_yr);

/* Copy all the field values of student1 into student2. */

student2 = student1;

/* Make a few changes to the student2 variable. */

strcpy(student2.name, "Frances Allen");

student2.grad_yr = student1.grad_yr + 1;

/* Print the fields of student2. */

printf("name: %s age: %d gpa: %g, year: %d\n",

student2.name, student2.age, student2.gpa, student2.grad_yr);

/* Print the size of the struct studentT type. */

printf("number of bytes in student struct: %lu\n", sizeof(struct studentT));

return 0;

}When run, this program outputs the following:

name: Kwame Salter age: 20 gpa: 3.5, year: 2020 name: Frances Allen age: 20 gpa: 3.5, year: 2021 number of bytes in student struct: 76

1.6.4. Passing Structs to Functions

In C, arguments of all types are passed by value to functions. Thus, if a function has a struct type parameter, then when called with a struct argument, the argument’s value is passed to its parameter, meaning that the parameter gets a copy of its argument’s value. The value of a struct variable is the contents of its memory, which is why we can assign the fields of one struct to be the same as another struct in a single assignment statement like this:

student2 = student1;Because the value of a struct variable represents the full contents of its memory, passing a struct as an argument to a function gives the parameter a copy of all the argument struct’s field values. If the function changes the field values of a struct parameter, the changes to the parameter’s field values have no effect on the corresponding field values of the argument. That is, changes to the parameter’s fields only modify values in the parameter’s memory locations for those fields, not in the argument’s memory locations for those fields.

Here’s a full example program using the

checkID function that takes a struct parameter:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

/* struct type definition: */

struct studentT {

char name[64];

int age;

float gpa;

int grad_yr;

};

/* function prototype (prototype: a declaration of the

* checkID function so that main can call it, its full

* definition is listed after main function in the file):

*/

int checkID(struct studentT s1, int min_age);

int main(void) {

int can_vote;

struct studentT student;

strcpy(student.name, "Ruth");

student.age = 17;

student.gpa = 3.5;

student.grad_yr = 2021;

can_vote = checkID(student, 18);

if (can_vote) {

printf("%s is %d years old and can vote.\n",

student.name, student.age);

} else {

printf("%s is only %d years old and cannot vote.\n",

student.name, student.age);

}

return 0;

}

/* check if a student is at least the min age

* s: a student

* min_age: a minimum age value to test

* returns: 1 if the student is min_age or older, 0 otherwise

*/

int checkID(struct studentT s, int min_age) {

int ret = 1; // initialize the return value to 1 (true)

if (s.age < min_age) {

ret = 0; // update the return value to 0 (false)

// let's try changing the student's age

s.age = min_age + 1;

}

printf("%s is %d years old\n", s.name, s.age);

return ret;

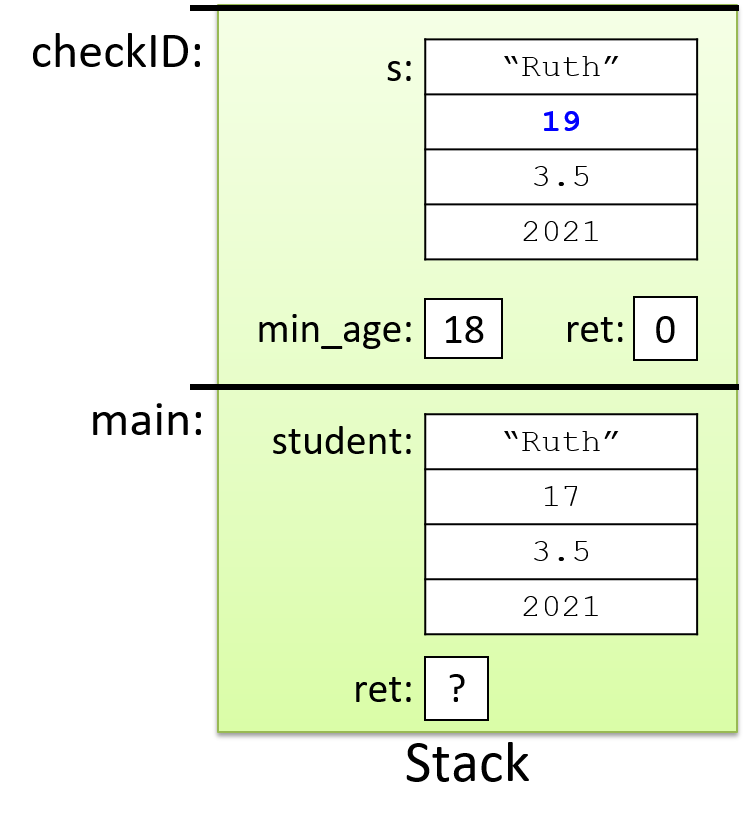

}When main calls checkID, the value of the student struct

(a copy of the memory contents of all its fields) is passed to the

s parameter. When the function changes the value of its parameter’s

age field, it doesn’t affect the age field of its argument (student).

This behavior can be seen by running the program, which outputs the following:

Ruth is 19 years old Ruth is only 17 years old and cannot vote.

The output shows that when checkID prints the age field, it reflects the

function’s change to the age field of the parameter s. However, after the

function call returns, main prints the age field of student with the same

value it had prior to the checkID call. Figure 3 illustrates the

contents of the call stack just before the checkID function returns.

Understanding the pass-by-value semantics of struct parameters is particularly

important when a struct contains a statically declared array field (like the

name field in struct studentT). When such a struct is passed to a

function, the struct argument’s entire memory contents, including every array

element in the array field, is copied to its parameter. If the parameter

struct’s array contents are changed by the function, those changes will not

persist after the function returns. This behavior might seem odd given what we

know about how arrays are

passed to functions, but it’s consistent with the struct-copying behavior

described earlier.